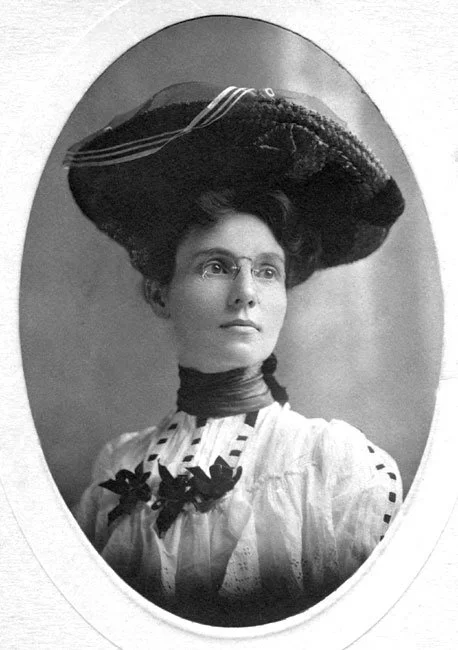

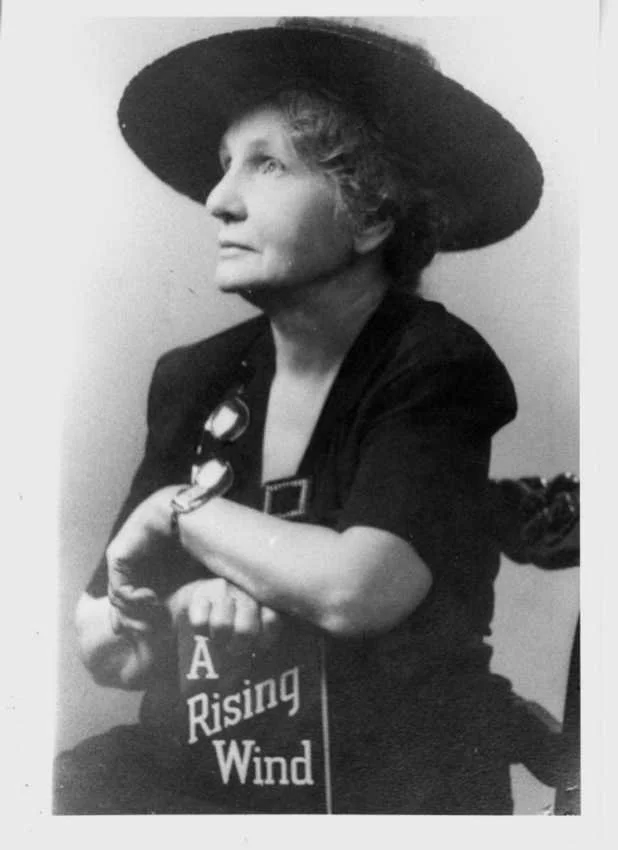

Bernie Babcock (1868–1962)

In 1903, Julia Burnelle (Bernie) Smade Babcock became the first Arkansas woman to be included in Authors and Writers Who’s Who. She published more than forty novels, as well as numerous tracts and newspaper and magazine articles. She founded the Museum of Natural History in Little Rock (now Museum of Discovery), was a founding member of the Arkansas Historical Society, and was the first president of the Arkansas branch of the National League of American Pen Women.

Bernie Smade was born in Union, Ohio, on April 28, 1868, the first of six children, to Hiram Norton Smade and Charlotte Elizabeth (Burnelle) Smade. Her family moved to Russellville, where Smade attended public school. On March 17, 1884, when she was fifteen, she read her impassioned essay at the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) Convention, which was published by request of the Russellville WCTU. She enrolled in Little Rock University, paying her way by working as the college president’s housekeeper.

Although she made excellent grades in school, Smade did not return to college the next year but instead married William Franklin Babcock, who worked for the Pacific Express Company, in 1886. For a short time, the couple lived in Vicksburg, Mississippi, where the society that had relied heavily on slavery in the recent past still retained many of the attitudes and customs of that time. Her observations there resulted later in the play Mammy, the first drama in which a slave “mammy” plays the leading role; it was later published by Neale Publishing Company of New York.

The Babcocks returned to Little Rock, where, after eleven years of marriage and the birth of five children, William died. His widow was determined to make a living by writing so that she could stay at home and raise her family; at night, she wrote stories and poems that she sent to editors across the country.

Her first book, The Daughter of the Republican, was published in 1900 and sold 100,000 copies in six months. It was followed by The Martyr (1900). These were “temperance novels,” describing the suffering caused by the consumption of liquor. Her books and emotionally charged tracts on the subject were credited with helping to bring about the national prohibition amendment in 1920.

Justice to the Woman (1901) and A Political Fool (1902) were political novels also about temperance. By Way of the Master Passion touched on the “fascinating story of evolution.” Babcock herself was interested in nature, and Darwin’s Origin of Species and the Bible were the first two books in her library after she was married.

When her youngest child started school, Babcock became society page editor for the Arkansas Democrat. She wrote features and, for a while, was the main editorial writer for the paper, though without a byline, which was standard newspaper practice at the time. Babcock was also the first female telegraph editor in the South.

After five years at the Democrat, she resigned to start her own project, becoming editor and publisher of The Sketch Book, “the most beautiful magazine in the South,” whose photography, paintings, stories, poetry, and music were original Arkansas contributions. Four issues a year were published from 1906 through 1909. In 1908, she also published the first anthology of poetry written by Arkansans, Arkansas People and Scenes: Pictures and Scenes, containing 100 poems and seventy illustrations.

Babcock moved to Chicago to work for a newspaper there, which serialized several stories she wrote, including “Daughter of the Patriot” and “The Devil and Tom Walker.” She also served on the staff of The Home Defender, a prohibition newspaper. She later returned to Arkansas, believing that to be a better environment for raising her children.

Babcock spent winters in New York City doing research in libraries and in the National History Museum. Her study of “submerged poverty people” (the unrepresented or unacknowledged poor) was introduced at a meeting of garment workers. It was used to inaugurate a strike for higher wages. Before the strike ended, 75,000 sympathy strikers marched on Broadway.

After reading a story in Ladies’ Home Journal about the love affair of Abraham Lincoln and Ann Rutledge, Babcock corresponded with the Illinois Historical Society and many persons who had known Lincoln personally. She became one of the country’s leading authorities on Lincoln, having conducted numerous personal interviews with his law partners and others, and published of The Soul of Ann Rutledge in 1919. This biographical novel was an international success, going through fourteen printings and translation into several foreign languages. It also was adapted into a stage play in 1934 and a radio play in 1953, when it was performed by the American Theater Wing.

Babcock learned through her research that she shared many of Lincoln’s beliefs, and she wrote four more books about Lincoln and his family between 1923 and 1929. She also wrote Light Horse Harry’s Boys (1931) about Robert E. Lee and The Heart of George Washington (1931) about the first U.S. president.

She used her love of nature and history to repudiate noted polemicist H. L. Mencken’s derision of Arkansas. Babcock decided in 1927 to “show ‘em by establishing a quality museum to belie the state’s reputation as a cultural backwater.” She first presented exhibits in a storefront on Main Street in downtown Little Rock. One such exhibit was King Crowley, a sculpted stone head containing eyes of copper with silver pupils and ears decorated with gold plugs, which had been “discovered” in a gravel pit on Crowley’s Ridge in Craighead County; thought to be an ancient artifact, it was later proven to be a fake, though Babcock was long a proponent of its authenticity.

Later that year, she secured the third floor of City Hall for the fledgling Museum of Natural History and Antiquities, which she financed with donations from friends. In 1928, Babcock wrote to Henry Fairfield Osborn, president of the New York Natural History Museum, asking for help in securing exhibits. He sent her a boxcar of mounted animal displays.

In 1933, when space was needed for Works Progress Administration (WPA) offices, the museum’s exhibits were crated and stored in the basement. Many of these artifacts were pilfered, and few were returned despite Babcock’s call for help to the mayor.

In 1935, Babcock became folklore editor of the Federal Writers’ Project, for which she did research on African-American and Native American history in the state. Surveys included interviews with almost 1,000 ex-slaves, at which time she attended all-night voodoo rituals in keeping with her interest in the supernatural. She wrote for Modern Mystic, a magazine in London, England, and was a member of both the American and British Psychical Research Societies.

By 1941, the last surviving Confederate soldiers of the Civil War had vacated the Arsenal Building in Little Rock City Park. With the help of businessman Fred Allsop and the promise of city government to provide a curator’s salary and funds to renovate the building, Babcock again opened the Museum of Natural History. Then in her seventies, she literally lived in the basement and often scaled ladders to paint murals of prehistoric scenes on the walls to enhance exhibits.

Thanks in part to Babcock’s influence, the city park was renamed in honor of General Douglas MacArthur, who had been born in the Arsenal Building. Babcock corresponded with MacArthur, and he and his family attended a ceremony at the park on March 23, 1952.

Babcock retired from the museum in 1953. She donated many objects to the museum, including the large marble statue of a woman, entitled Hope, which she had placed there in memory of her husband. She itemized other items and billed the museum $800, with which she planned to start a new life at the age of eighty-five.

Her new life began in a small house on top of Petit Jean Mountain, where she began to paint and continued to write. In 1959, she published her only volume of poetry, The Marble Woman. She died at home on June 14, 1962, a few weeks after her ninety-fourth birthday; a neighbor found her sitting with a manuscript in her hand. Her mountaintop retreat had been aptly named—Journey’s End. She was buried in Oakland Cemetery in Little Rock.

This entry appears in the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas.

Photos credit Special Collections, University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Marcia Camp, and UA Little Rock Center for Arkansas History and Culture.